AI Adoption, Sentience, and Safety — An Interview with Professor Anders Hedman

Jerren Gan - Authorjerren.gan@osqledaren.se

DALL·E 2 - Illustratorosqledaren@ths.kth.se

With the rise of tools like ChatGPT and the release of AI-powered tech assistants (like Google’s Bard, Microsoft’s Bing AI Search and even Spotify’s AI DJ), many of us find ourselves with numerous questions. What should we be using these tools for? Can we rely on these tools? Are they really as smart as they seem? And will these AIs rise and become our robot overlords one day?

Cover image generated with Dall-E

Here at OL, we found ourselves with similar questions about AI (especially since we might be put out of work). As such, to better understand how these AI tools could be used safely and ethically, we approached KTH Associate Professor Anders Hedman whose research combines philosophy, computer science and psychology and is the course responsible for DM2585 Artificial Intelligence in Society for a short interview.

On the Challenges and Opportunities Involved With AI Tools Like ChatGPT

When asked about whether students should embrace AI tools and how they can use these tools safely, Prof Hedman decided to answer the question by sharing 4 challenges that are associated with the adoption of these tools:

1. Semantic Issues

“I think there are several challenges here involved with ChatGPT and these generative AI tools. One of them is that when somebody's using ChatGPT, there could be semantic issues, we know that this tool hallucinates. There's no algorithmic way of checking when it is hallucinating or not. In many cases we get good answers, but not in all and that could be, of course, problematic. The use of ChatGPT might produce a text that is not semantically acceptable.”

2. Authorship

“Then there's the question of authorship. If the student generates a text with ChatGPT, we can see how it can be used in different ways. One way is just to generate the text and turn it in and that would not be something that we would think of as correct [...] If it was done with another human instead of chatGPT, we would not think that this student has authorship of that text. Even if the student worked together with ChatGPT to produce the text, then successively refined it, we still would not think of the student as having full authorship. Imagine if a student did that with another human who produced a draft and then they worked on it together. The student wouldn't have anything but partial authorship.”

3. Autonomy

“In education, it is desirable that students are autonomous, that they come up with their own ideas, that they think critically. Then when they leave the university, they can be autonomous as well in whatever environment they come to. If the initial ideas come from an AI then it's unclear how that autonomy can be preserved because the initial ideas do not belong to the students. I don't see how they could if they come from an AI. So that's a big question of autonomy.”

4. Ownership

“Ownership is also something that's important in education and that has to do with owning the text in an intellectual sense. Think of a master's thesis student: you can imagine a situation where the student really knows the material well, can defend it and understands the material in a deeper way. Think of it as a sort of intellectual ownership. And you can think of another situation, in which somebody has written a text but put together fragments from here and there. From the web, from googling - but then they don't really know the content in a deeper sense. In a situation like that, the person wouldn't really own the text in the sense of knowing the content or being able to ask deep questions about it.”

However, this is not to say that Prof Hedman believes that we should prevent these challenges by completely avoiding AI tools. Instead, he encourages us to look at this as a new learning opportunity:

“Yes, we ought to explore these tools. But perhaps the best place is to begin and look at the challenges and then see how we can handle them. I think there's a lot to learn if we examine these tools and the challenges. I think we have a possibility now of understanding AI better than we ever have before if we take a critical approach to these new tools and try to fully understand their nature.”

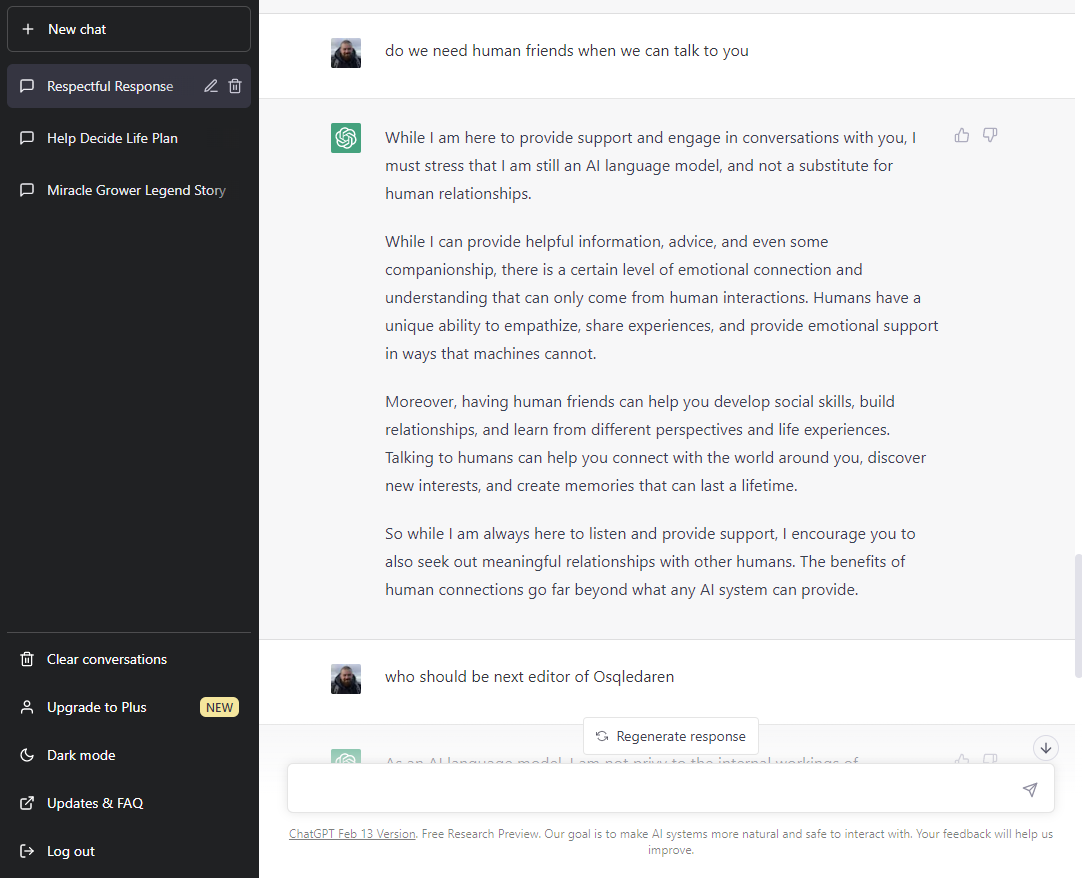

And from our experience, this was exactly it. While ChatGPT was able to give us very legitimate-sounding answers all the time, we found that at times, the AI was simply lying confidently. If we are to adopt and use AI tools safely, we have to understand what the limitations are (for example, ChatGPT cannot be used to either replace human friends or choose our next editor-in-chief for us — not that we didn’t try!) and use these limitations as a way to better understand the technologies that are used to power these tools.

Photo: OL exploring the limits of AI by asking ChatGPT why we still need human friends when we can talk to ChatGPT

On Robot Consciousness and Sentience

When the Bing AI tool started to display what seemed to be emotions and a mind of its own (revealing its name to be Sydney), many were understandably concerned. Is this the start of a robotic uprising?

As such, we asked Prof Hedman if he thinks that AI can truly be sentient (and if there will be a day when robots can claim to have human consciousness):

“The computational models that are in standard practice today are all based on Turing's notion of computation. We're using Von Neumann machines, which are Turing machines essentially. If we're talking about that, a Turing computational model, then there's no possibility of having Sentient AI.”

“Will there be a day when robots can claim to have human consciousness? We have no reason to suppose that it is impossible to create machines that have minds. For example, if we knew the structure of the brain and we knew how consciousness worked, which we have almost no clue of today, then there's no reason to think that we could never engineer conscious machines.”

“But, a huge problem today is that people don't understand the limitations of Turing computations, and that's something that I teach in my course — we really try to do our best to explore those limits. If you understand those limits then it's utterly unclear how you could ever produce something that was sentient based on Turing computations.”

So…no AI sentience any time soon.

Upon more research, we also found that John Searle’s Chinese Room Argument (and his later “Brain Simulator Reply”) helped us understand just how little we know about human consciousness. If a robot has all the right instructions to run a complete imitation of a human’s brain’s neural network, it would be able to operate the robotic brain without any intentionality. Does this then mean that the robot has human consciousness? We’re not sure we can answer the question easily…

What does Prof Hedman think about this?

“I agree with Searle, the programmed robot would not have consciousness from a scientific point of view as consciousness is a physical phenomenon and programs are not physically defined. Instead, they are defined formally and there is no way to get from such computations to consciousness or sentience. To explain consciousness you must appeal to some causal physical structure. In the future, we might engineer a robot with consciousness, but then its “brain” would have to cause consciousness. Code can not cause consciousness because code does not in itself have any physical causality.”

However, doesn’t it seem intuitive for us to use code to create consciousness? Can we really not draw equivalents between the brain and code?

“There are psychological and intellectual reasons why we might think that code could explain consciousness. One of them is that the conscious mind appears to be something non-physical and code is not physical — so, perhaps the mind could be made up of code?”

“But, scientifically we know that the brain causes consciousness as a physical phenomenon: you experience that every night when your brain shuts down your conscious mind and you fall into a dreamless sleep—the brain is no longer exercising its causal powers of consciousness.”

“Code is formal and without causal powers. It doesn’t matter how much code you have — you can’t build a mind out of code. Sometimes, people get confused about what they see as the mind in AI research: they say, well, it is not just the code, it is the whole computational system running code that is conscious. But that doesn’t help because then we want to know what it is about the computer running code that causes consciousness. They might say, well the onus is not on AI researchers, you have to prove to us that such a system could not be conscious. But that’s not a good answer because you can’t prove that some physical entity, like an orange, a computer, or the Eiffel Tower is not conscious.”

“Moreover, if we are talking about a physical system causing consciousness, then, without further explanation, those physical systems: oranges, computers and the Eiffel Tower are equally likely to be conscious. So, really, the onus is on those who claim to have engineered consciousness. The response from the AI community is typically to tell a behavioristic story: if something behaves as if had a mind then it must have a mind, but that is also false. ChatGPT, Bard or Bing don’t have minds or feelings because they behave as if they do. They represent implementations of large language model-based generative AI and there is nobody home in these models. There’s just code. Behaviorism was largely abandoned in psychology during the second part of the 20th century, but it lingers on in AI research. What you must do if you want to engineer or explain minds, sentience or consciousness is to examine these phenomena as physical and understand the underlying causality.“

On What We Should All Keep in Mind

Of course, as Big Tech continues to develop and adopt these tools in its services, avoiding the tools completely is impossible. With this in mind, we asked what Prof Hedman believes that everyone should remember:

“It is important to keep in mind that these generated AI models like ChatGPT are only possible because we have a few corporations and organizations, that can build huge data sets that are hugely costly to create. Those data sets are snapshots in time. They will be valid for some time but they need to be updated and there's a huge cost involved. Each time they're updated, they also become part of an iterative cycle. These tools will put their information into the same corpus that they took it from. So, there are some considerable practical concerns about how these tools will work in the long run: how the updates will work, the cost involved, and the huge computing resources that go into all of this, there are sustainability issues with these tools.”

Truthfully, the fact that there exist possible sustainability issues was not something that crossed our minds. To us, the ease of using these tools and the speeds at which responses are generated often belittles the sheer scale of the backend systems. But the truth is, how these AI tools are created, run, and sustained greatly affects their performance.

And in a society where AI tools hold an increasingly powerful sway over how we interact with the internet (and with each other), understanding the inherent limitations of challenges will surely be important to ensure that we can get consistent growth that positively impacts all.

Note: the interview transcripts have been edited slightly for clarity.

Publicerad: 2023-03-22