The Cathedral of Science

Alexandra Andersson - Authoralexandra.andersson@osqledaren.se

Amanda Andrén - Photographerosqledaren@ths.kth.se

Carl Housten - Photographercarl.housten@osqledaren.se

Cornelia Thane - Illustratorosqledaren@ths.kth.se

The acoustics in the old reactor hall, 25 meters below KTH, are quite surprising. History echoes in the walls, whispering stories about Sweden's entry into the atomic age. Today, R1 is no longer the stage for ground-breaking research, but instead fulfills KTH's motto with brilliance, creating experiences beyond the ordinary.

I took the elevator down to KTH R1 to hear the history about Sweden's first nuclear reactor, a scientific and cultural heritage which is often being forgotten. Once there, I found that R1's history did not end when the reactor was shut down. In reality, that was only the beginning.

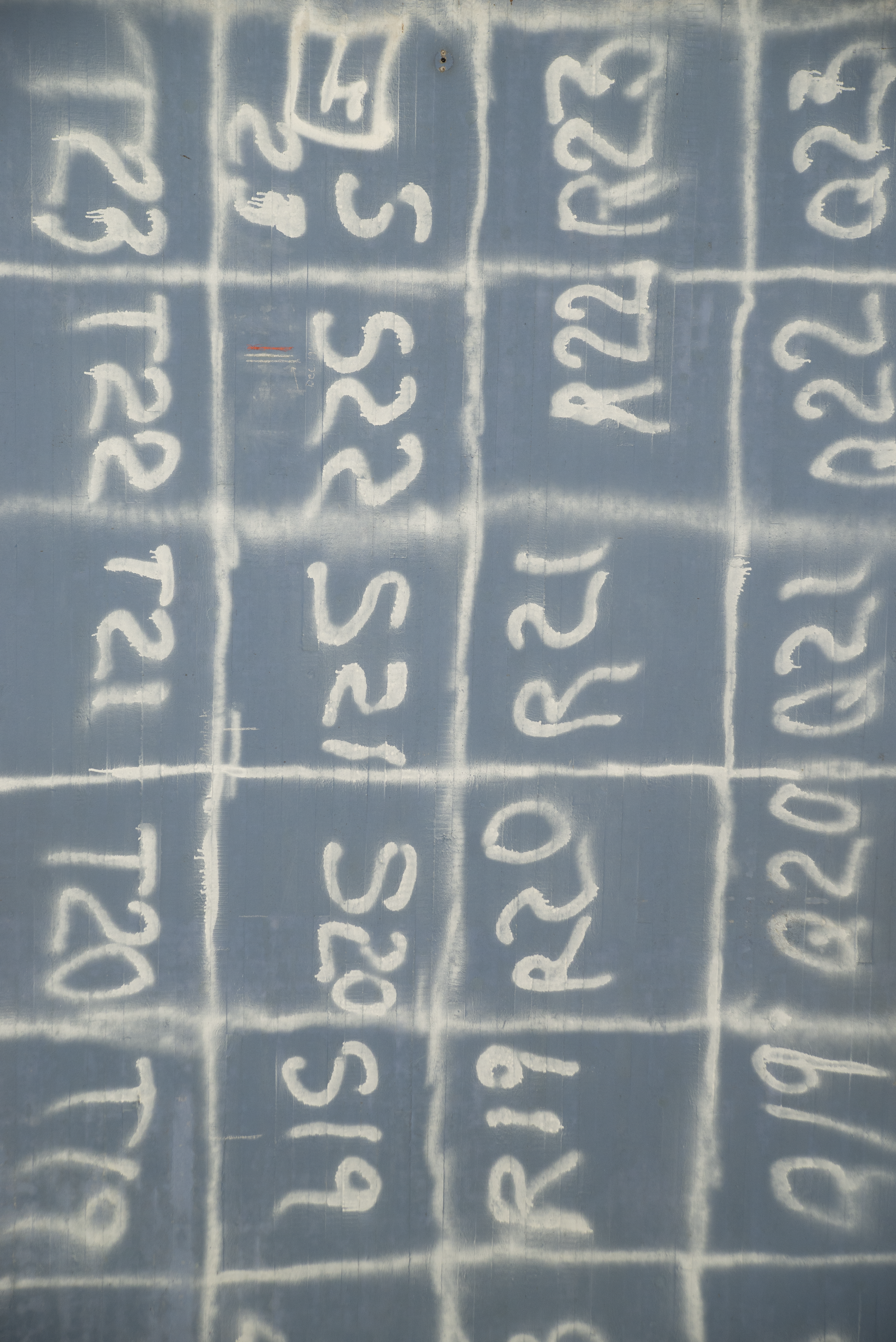

After contributing with valuable research results and radioactive products used in healthcare for 16 years, R1 was shut down for good in 1970. Over the next decade the resistance against nuclear power grew. In the 1980s the reactor was demolished and its remains were put in the low-level waste repository in Forsmark. This was also when the characteristic grid, covering the walls, the floor and the ceiling of the reactor hall, was created. After measuring every single square with sensors, it was confirmed that the radioactive radiation in the room was below all limit values, and it was thus cleared and no longer counted as a radiation room. But the grid remains, as a reminder of what once happened here, and an assurance that the reactor hall today is safe to visit.

Then followed a couple of years when this unique place fell into oblivion. For a while there were ideas about building a data center here, or perhaps a storage for the library at KTH, but it was not until 1998 that something happened. That was when KTH Medieteknik (Media Technology) came into the picture. One of the initiators was Leif Handberg, lecturer in media technology and current superintendent of R1. He talks about how it all started:

“There had been an announcement from the National Agency for Higher Education that you could apply for money to collaborate with artists, from universities and colleges. During the 1990s, in the field of media technology, we had seen this supernova of new communication possibilities that appeared with the internet. One of the ideas we came up with was that we would like to set up an experimental scene, a creative meeting place where we could meet between different disciplines. And then I knew this place existed.”

In May 1998 KTH Medieteknik created its first installation in R1.

“It was science and art in many ways”, Leif describes.

At the same time, they also installed internet in the reactor hall, which enabled everything from video conferences and digital theater to live music down there. In the years that followed, at least one event per year was organized, and it became more and more clear what potential there was in this once forgotten place.

Akademiska Hus owns KTH R1, but since 2007 KTH has been a formal tenant here, with Leif Handberg as project leader. Since July 2020, the reactor hall has been part of the “Gemensamma verksamhetsstödet” (eng: University Administration of KTH), where Leif now also works part of his time, to ensure that R1 comes into its own and contributes something positive to KTH. There is certainly no shortage of creativity:

“We have had theater, opera, dance, seminars, presentations on research within technology - not least in energy and reactor physics. Sometimes we have had conference dinners, as representation for KTH.”

Many events are internal, but there are also those open to the public. In October 2021, for example, "Kafka's archive", a theater performance, was staged.

“Now we run it as a kind of mixture between museum, cultural center, seminar room, studio, lab, exhibition hall and more”, says Leif and calls out the enormous width that the unique place has today.

When Leif somewhat cryptically says that he is going to prepare something that he would like to show me and the photographers, we take the opportunity to climb the stairs in the office part of the hall. Up there, we are so close to the sky-blue roof that it feels like we can almost touch it, and we have a view of the entire reactor hall. When we take the stairs back down, we are all excited about what we are going to see.

“I’ve gotten to know some of the people who worked here when the reactor was running. Now they are starting to disappear due to age, unfortunately. Professor Karl-Erik Larsson passed away five years ago, aged 94. We celebrated his 90th birthday with a party down here - it was great! He gave a lecture about "My life with neutrons" – but afterwards he came to me and said: "This was probably my last lecture"”, says Leif.

Karl-Erik Larsson came to AB Atomenergi in the late 40s, as a young researcher. He eventually became professor of reactor physics at KTH, and then also program manager for the physics program.

“He told me that they sometimes called this the "cathedral of science", and I think that's quite neat. And what do you need in a cathedral? Well, an organ!"

An organ is exactly what now stands next to the reactor. More specifically, a Wurlitzer type pipe organ, from 1926. It is a cinema organ, and originally it was installed at Skandiabiografen (the Skandia cinema). It is the association Skandiaorgeln that owns it, but today KTH allows space for it in exchange for it being used. In R1 everything from organ concerts to silent film screenings with a cinema organist are organized.

“What's cool about this is that even though it's called a silent film, it's by no means silent, but when it's done well, you don't think about it”, says Leif.

Leif is eager to show us the organ in more detail.

“We have built our organ house somewhat like a replica of the reactor, so it has sort of the same shape and colors. It's a little flirtation with history. Basically it's like a regular pipe organ, like those found in churches, but this one has a few other things too.”

The organ has seven pipes, and with the help of the pipes it can imitate a surprising number of sounds. In addition to the given, it can sound like anything from a violin or trumpet, to a xylophone, cymbal and church bell. There are even more unique sounds, such as sirens, "waves against a shore" and, not to be forgotten, "the galloping horse". All these sounds are produced through air pressure only.

Although Leif is not an organist himself, he has learned a well-known piece, and when he plays the melody for the British musical "The Phantom of the Opera", the description of the reactor hall as the "cathedral of science" feels much more obvious. The magnificent notes make the room vibrate and the melody that wanders up the walls envelops the entire room in a powerful feeling.

“You have to be able to play something,” Leif says with a shrug and then quickly dives further into the fascinating instrument.

“An organ consists of four parts: first you have a large fan that provides air pressure, then a soundboard with keys where you control everything, then a control system that makes sure air gets into the right pipe, and then we have everything that sounds. This control system dates back to 1926, and you could basically say it was like an early telephone switchboard. Back then there was a tube for everything inside the organ house, but now everything goes through a category 5 cable. It's now completely digital, this control system. And that's what's so cool about this organ."

Even though the control system is now completely digitized, it sounds exactly the same as before. Today, the system is based on so-called midi signals, and this brings new possibilities.

“This means two things: when someone plays the organ, you can insert a midi interface and "suck" it into a computer. Then, when the organist is no longer here, you can play that file again and it will sound just like when the organist played. So we actually have a self-playing organ here! The other thing is that you can control the organ in other ways than from the playing table. Anything that can give off midi signals can control the organ, and we have now started to experiment a bit with that.”

As with everyone else, the pandemic has put a damper on the activities in R1, but there are several plans for the future, which will become reality if the situation allows it. Not least, there will hopefully be a few more events involving the organ.

“What we are most looking forward to right now is the staging of KTH's own opera, based on the book "The Tale of the Great Computing Machine'', written in 1966 by KTH's Nobel prize winner Hannes Alfvén”, says Leif.

The planned premiere for the opera is in December 2022, and it is a collaboration between KTH and Stiftelsen Vadstena-Akademien. It is the first time ever that an opera will be staged in the reactor hall. More information about the opera is available at kth.se/thetale.

I leave KTH R1 with many more stories than I had ever hoped for when I got there. Not least the story of Sweden's first nuclear reactor that died and came back to life, and developed into a cultural heritage in more than one way. The story of a sometimes forgotten place where history seems to have stood still in a certain sense, but where new history is also constantly being written. I am already longing for the next opportunity to experience the grandeur of this cathedral of science.

Publicerad: 2022-09-15