Milked oats: The Oatly Story and Their Controversial Investors

Adam Särnell - Authorsarnell@kth.se

Isabelle Holmér - Illustratorosqledaren@ths.kth.se

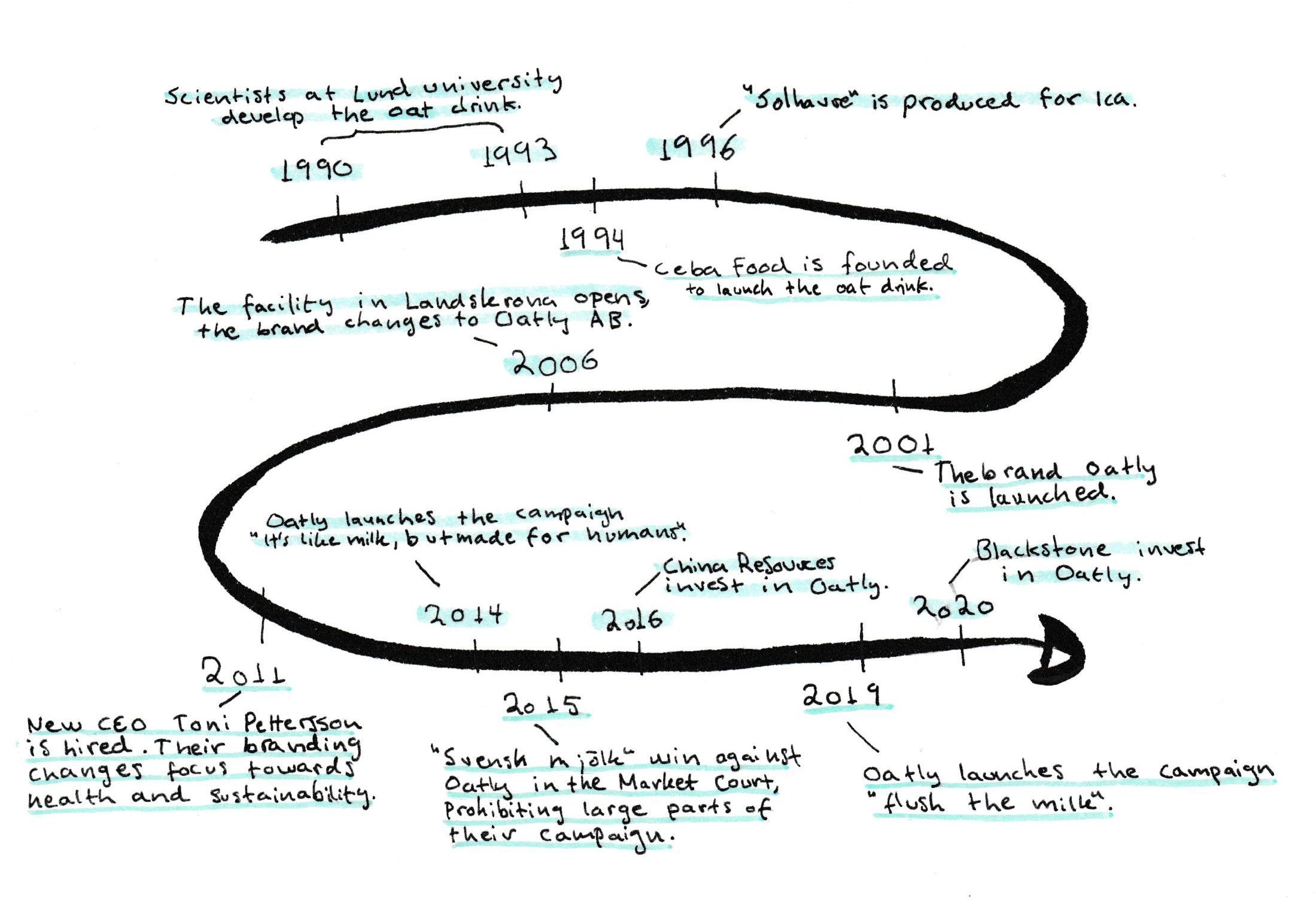

A debate that has gradually engaged people all over the world is the one regarding Oatly, the Swedish company known for producing oat-based alternatives to dairy products. While a large portion of the debate has revolved around their controversial marketing and their rivalry with the Swedish milk industry, a lot of their recent attention has been drawn due to some of their investors: Blackstone and China Resources.

Oatly have branded themselves as an environmental-friendly company and as a healthier alternative to dairy products. The message towards consumers has been that by choosing Oatly’s products over dairy you are both actively helping the environment, because of their products’ lower carbon footprint, and choosing a healthier lifestyle. In 2014 the Swedish milk industry took them to court where Oatly lost. This stopped them from using slogans such as “no milk, no badness” and they were also not allowed to market their products as healthier than dairy.

Cow’s milk made its way into the Swedish “folkhemmet” during the last century where the milk industry, receiving financial support from the Swedish government, has a long history of marketing milk as a healthy drink for all occasions and as an indisputable part of the Swedish diet. It is only in recent years that this view of milk in Sweden has been questioned on a larger scale – partially due to Oatly’s marketing.

Oatly have been transparent with their goal to replace milk and it has been the motivation behind them choosing to portray milk in a negative manner instead of lifting the benefits of their own plant-based products. Meanwhile, farmers and other parties have raised concerns that this strategy has been polarizing the discussion and not taking into account that growing crops and raising cattle both are essential parts of the Swedish agricultural ecosystem, that the issue is more complex than what Oatly’s campaigns show. There are many things to consider depending on if you focus on the carbon footprint, the biodiversity or both.

For example, in one hectare of land you can farm much more oat than you can produce milk, the drawback is that conventional farming risks the future fertility of the soil because of its often one-sided, frequent harvests. Meanwhile, a natural way of improving biodiversity and the quality of the soil is having more grazing cows, however, during the course of a cow’s life and by eventually being a part of the meat industry, cows have a substantial negative impact in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time cows eat residual products from the oat drink production and produce fertilizer that is used when growing oat. That is not to say that oat will be dependent on cow fertilizer in the future, although the use of synthetic fertilizers is a whole debate in itself. In the end there is probably room in the future for both cows and large scale oat production – only that the focus from now on should be more about finding a sustainable balance between the two.

Nevertheless, leading scientists agree (referring to the IPCC and journals such as Science and Nature) that the consumption of animal products has to decrease globally in order to adopt a more sustainable way of life, and a big challenge is that people’s dietary patterns will not change unless they are given alternatives they can incorporate into their daily lives – without having to sacrifice too much.

In many people’s eyes, Oatly’s products have been that alternative. A way for them to feel good about themselves regardless if they have made other changes to their consumption as well. Buying a box of oat drink to pour in your coffee totally justifies that half a kilogram of red meat you bought with it, right? Either way, Oatly has not only been a popular option amongst lactose-intolerant customers, their products have also been a prime example of that when everyday people are given a good alternative they have no problem with breaking habits and adjusting their weekly shopping list. A Swedish food blogger wrote: “We did not stop downloading music illegally because the anti-piracy agency sent out threats, it was because Spotify came along and made it easier and better to stream”. In the same sense, he implies that the decrease in milk and meat consumption we are seeing in Sweden is not happening because people suddenly discovered the products’ impact on the climate (this has been well known for many years) but that it is because there are finally more climate-friendly options that are good enough that consumers are willing to change their habits since the trade-off does not feel as significant.

This is the reason why many customers were disappointed when they found out that companies like Blackstone and China Resources, that both simultaneously invest in businesses harming the environment, are large stakeholders in a company that for many years have claimed that they are fighting for the environment. This dimension to the debate revolves around the following two sides: the side saying that Oatly is hypocritical by doing this and that it proves that companies only have an environmental image because it is trendy, and the other side defending Oatly claiming that this is an attempt of “guilt by association” and that these investors actually are a good thing.

Blackstone is one of the largest investment firms in the world and the company has stakes in hundreds of companies worldwide in a wide range of sectors: real estate, pharmaceuticals, fashion, banking, ICT, hotels, infrastructure – only to name a few. The 200 million USD (1.8 billion SEK) investment this year gave them roughly a 10% stake in Oatly and to put this number in perspective, Blackstone announced in their 2019 annual report that they ended the year with 571 billion USD of assets under management (AUM) which makes Oatly a tiny 0.0003% of their current assets.

It is not the first time Blackstone’s business ethics have been questioned, one example from last year is when the UN accused them of contributing to the ongoing global housing crisis. However, the reason why Blackstone’s investment has caused a commotion amongst Oatly customers is mainly that they own stakes in two Brazilian companies accused of contributing to the ongoing deforestation in the Amazon rainforest. One of the companies is a logistics and resource extraction company called Hidrovias do Brasil, known for aiding Brazilian farmers and other companies in transporting their products through the country – soybeans, for example. The government of Jair Bolsonaro has in recent years implemented an aggressive strategy to turn the Amazon into profitable agribusiness and the accusations against Hidrovias includes both facilitating the soy business expansion in the rainforest and aiding the government in developing the controversial highway BR-163 that runs straight through the Amazon. Blackstone has denied these claims, insisting that Hidrovias is operating to the highest sustainability standards possible.

The other controversial shareholder is China Resources. A Chinese state-owned multi-industry company that, besides owning 30% of Oatly, also owns businesses within a variety of industries like energy, food, construction and healthcare. Notably, the company owns and maintains a number of coal power plants through multiple regions of mainland China and it is also the monopoly holder of the importation of meat to Hong Kong.

Critique aimed towards Oatly for taking in these investors boils down to them being hypocritical, selling out to the highest bidders and essentially letting their customers down. After all, if you as a customer have bought a product specifically because the company behind it claims to be benefiting the environment, finding out that the money you have spent ends up profiting companies that actively invest in ways that harm the climate is bamboozling to say the least. Customers have expressed their frustration over it already being difficult to find good, sustainable alternatives and that Oatly’s actions limit their options even further. But is it completely a bad thing that these companies are starting to invest in greener options?

Oatly’s response to the critique is that them choosing Blackstone as an investor has been a well-thought-out decision from the start. They do not deny Blackstone’s alleged negative impact on the environment, instead they present another line of reasoning. They argue that to be able to reach global climate goals they “need to speak a language that the capital markets can understand”. In other words: while many consumers might resonate with Oatly’s message and therefore support the company, the money required to expand in the pace necessary to reach the climate goals can only be acquired by showing the world’s established, capital-heavy players that vegetal products is an industry worth investing in. Their plan is that by proving themselves as a viable option for investment firms they will redirect funding from non-environmental-friendly industries in the process. This is a strong argument in theory but until success is proven their customers can only hope that their strategy is as game-changing as they say and that those 0.0003% creates the ripple effect needed.

The discussion around whether Oatly should be blamed for what their investors are doing is more of a philosophical one. China is not the only country whose state-owned company owns coal-driven power plants, Sweden’s does too through the power company Vattenfall. Would that make it controversial if news broke that Vattenfall decided to invest in Oatly? Each year, the coal power plants that Vattenfall owns in Germany are emitting more greenhouse gases than the whole country of Sweden, all while China has since 2011 burnt more coal than all other countries combined – so who can judge what amount of coal is accepted or not? Should you take into account that China is the country spending the most money in the world on clean energy R&D? Or that the energy production within Sweden is 98% fossil-free?

People defending Oatly say that it is naive and unrealistic to demand an economy where you may only receive investments from 100% pure investors with no negative associations whatsoever. They also suggest that investing in disruptive, forward-thinking companies is doing more for the environment than, for instance, suing them. Nonetheless, this line of reasoning should make any person ask themselves: If the end goal justifies the means, how “bad” does a potential investor have to be for a company like Oatly to turn them down?

Publicerad: 2020-12-08