Does my toaster work in the freezer?

Ayan Allwan - Authorayan.allwan@osqledaren.se

My Andersson - Photographermy.andersson@osqledaren.se

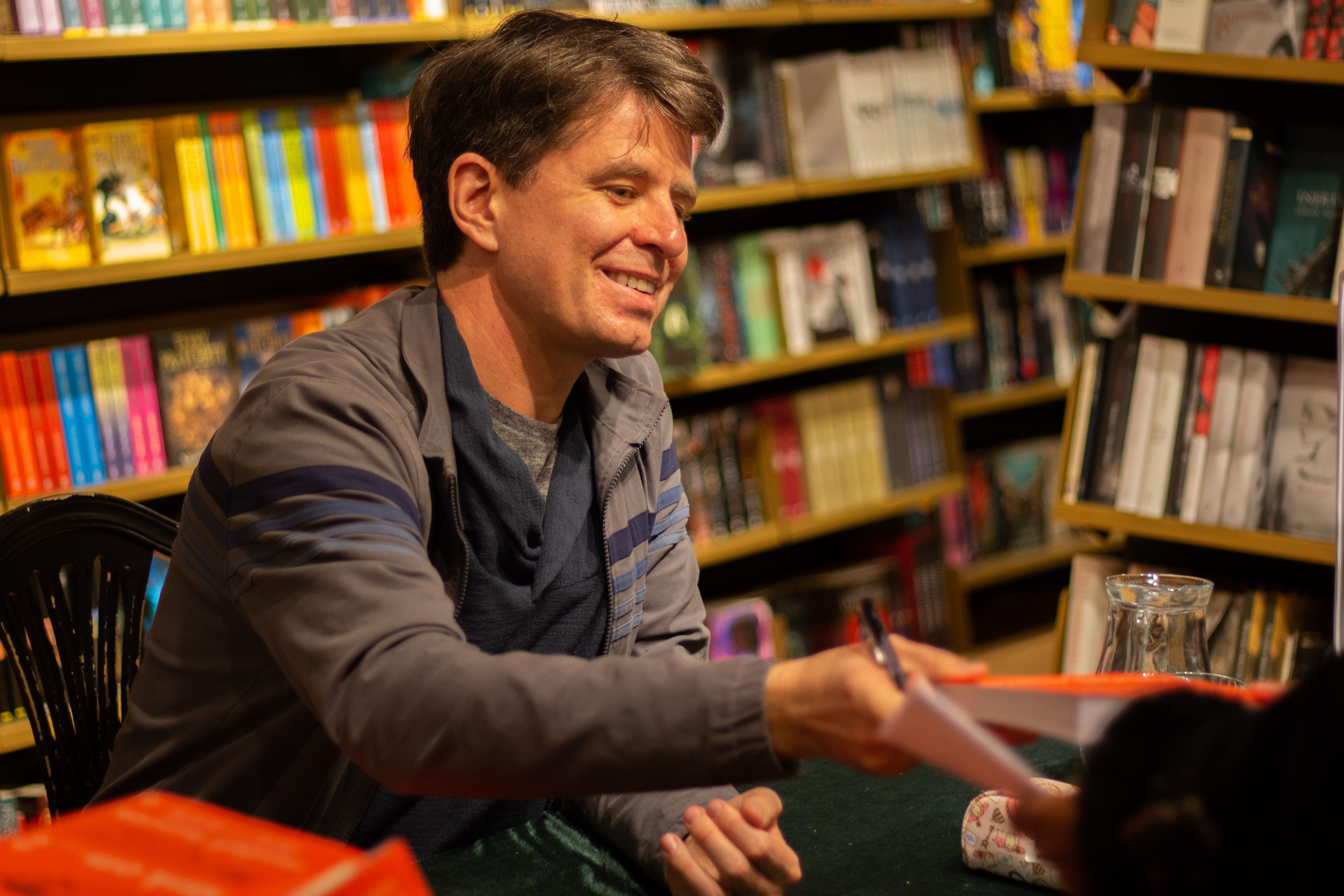

Ever wondered how many bananas it takes to power a house? How many fireflies to match the brightness of the sun? Author, cartoonist, and engineer Randall Munroe was in Stockholm for his book “What If? 2”, a collection of some of the many intriguing viewer-submitted questions he answers on his blog “What If?”. Osqledaren interviewed him right before his book signing.

Randall doodled and studied physics in college, and worked at NASA before and after graduation. He later chose to focus full time on his stick-figure webcomic XKCD, which primarily made up his blog at the time. The ambiance in his publisher’s office in christmas-clad Gamla Stan was cozy, cut up saffron buns and coffee laid on the table, and Munroe tells us Stockholm is actually further north than the capital of Alaska! What else is there to find out from this man?

Do you want to tell us a little bit about “What If?” for anyone that hasn’t seen it?

I didn't really set out trying to answer people's questions. But since I was doing comics that are about math and science topics online, people would just ask me to settle arguments they were having about science things. It would be like, could you catch a ball that was thrown at 90% of the speed of light? Or, if Superman flew really fast, would he create a shockwave that did this or that? I'd drop everything else I was working on and spend like 8 hours coming up with an answer for them. And then I started thinking, if I'm spending this much time trying to figure these questions out, maybe other people would like to see the answers too. So I just put up a note on my site saying “You can send me questions!”, and started posting and putting together the first “What If?” book.

When did you think, oh, that actually works, people are excited about this?

There's a program at MIT where people who are interested in a certain topic can come and teach a class to high school students, and I decided to teach a class on energy. Energy is a weird concept, and I thought that it would be fun to try to explain to high schoolers. I found that the parts that were more like the normal physics lecture made me sympathize with my own professors. They would try to work through subjects with students who weren't necessarily interested or excited about it. Toward the end I thought, let's just try applying this to some real life questions. What if there was a fly that was made of antimatter and a fly that was made of matter, and they collided in this room? How far away would you have to be to survive? And suddenly everyone perks up, all of them were interested!

I remember having these boring introductory classes when I started university - and then reading “What If?” and going through the same process that you might have during your research: 50 tabs and 27 PDFs open on my laptop, suddenly realizing it’s 3am! Why do you think that was so much more exciting than my university classes?

I think there's something inherently satisfying about having a puzzle and realizing you have the tools to solve it. I don't know why that is. There are lots of questions that everyday life doesn't give us the tools to answer. Like, if the moon collided with the Earth, what would it be like? You can sort of guess at it, but I feel like it opens up a lot of the world when you have these tools that let you find answers that you can't get through ordinary experience.

Do you think there's a way to combine our education with humor and absurd questions?

I think so. Teaching is really hard and I don't know what the right answer is for getting every kid interested in something or whether that is even a goal that makes sense. The way I go into it is just to try to share things I find interesting and say, if you like this stuff, here's what I've learned, here's what I've found. But you can't apply the same tone and the same material everywhere. A lot of the time what is funny or what is a useful reference for people varies depending on if people grew up watching the same TV show or like the same kinds of jokes as you. If you're writing a textbook that's going to be used by everyone, you have to sometimes pare it down to the more dry, abstract stuff, in order to make it accessible. Sort of like the emergency exit signs. You don't want to make them too fancy, right?

We talked to some physics students at KTH who said that some of their professors end their lectures with your XKCD comics. What do you think about that?

It always intimidates me a little bit. I remember when I was doing my comics at the very beginning, and I would do a comic about professor so and so's algorithm. And someone would say, hey, I'm actually taking a class from this professor, and they used your comic in their slides! And I'm like, “oh, no, did I get the math right? I was just doing that for my friends, not for the actual experts!” I've had to learn to adjust. The people who know way more about it than me are also going to read it. So I have to be really careful to get things right.

Does that show anything about their teaching? They think they need something more to entertain the students?

I don't know. There's just something really satisfying about finding a way to explain ideas in a different context, in a way that captures all of its subtleties. One of my favorites was when I was trying to explain how fast the space station goes in orbit. If you stood at one end of an (American) football pitch and the ISS was going overhead, and just as it passed you fired a rifle across toward the other end - the space station would cross the whole field before the bullet made it 10% of the way. I was talking with Colonel Chris Hadfield, who was the commander of the ISS, and he mentioned that he uses that to explain to people how fast the space station goes. That was the highest honor I've ever had, an astronaut using my analogy to explain space!

Do you remember ever sitting in boring lectures and thinking, what if..?

Yeah, for example I would need to figure out some number, like the mass of the moon. I could only use the material I had with me, which would be my textbook. And so I was sitting there being like, “OK, how can I figure this out?” And I would sort of forget about the original thing at some point and just continue to work on that until class ended and then be like, oh, I should have paid attention, I completely tuned out for 45 minutes.

Do you think that it gets harder to come up with absurd questions, now that we have phones and we can just look up the mass of the moon?

I remember when phones first started having contact lists, and suddenly you didn't have to memorize phone numbers anymore. That was about when I first got a phone. People said that our brains are atrophying because we're not learning people's phone numbers anymore. And I was like, no, I can now use that space for something else! And I still feel that way. It doesn't stop you from going down rabbit holes of trying to figure things out. I'll still have questions that I think will be easy to google - and then they’re not.

Do you ever come across these crazy hypothetical questions in your day to day? Do you think about putting your toaster in the freezer when you're having breakfast?

I think part of what's really fun with doing “What If?” is that I don't come up with the questions. It's hard to come up with them in the same way it's hard to come up with an idea for a chair design. A lot of the questions that I answer in “What If? 2” come from little kids. Those are actually better in general, because kids are curious about stuff that I assume I understand already. I think that adults, when they ask questions, try to make sure they don't look foolish or like they don’t know what they're talking about. They want to ask good, sophisticated questions. They're reluctant to ask the really simple ones. Sometimes those are really hard to answer. That makes them the best questions.

Publicerad: 2023-03-18