Will KTH Go Bankrupt in 2026? The situation is more complex than that

Haoyue Liu - Illustratorhaoyue.liu@osqledaren.se

Filip Axelsson - Authorfilip.axelsson@osqledaren.se

KTH is currently in a serious economic crisis. KTH is investigating the future of Campus Södertälje and Kista. At the Union council at the end of September, a council member asked the President of KTH, Anders Söderholm, whether KTH would go bankrupt in 2026. How will this affect the students and their education? Should the students be worried? Osqledaren has investigated, and the situation is more complex than you think.

At this point, most students and teachers of KTH are aware of the economic problems at KTH. Fewer know the reasons behind the crisis and what consequences this will have for the education and the students. Most visible are the ongoing discussions about the future of Campus Kista and Södertälje but the effects are bigger than just those.

To get an understanding of the situation, Osqledaren met the Head of Economy at KTH, Susanne Odung, for an interview:

The interview is shortened, edited and translated from Swedish.

Describe the current economic situation at KTH.

— As a result of the high inflation that we are seeing right now, KTH is facing certain financial challenges. It is not unique to KTH. Many other organizations have these problems. I believe the challenges facing KTH are of such a nature that we can still manage them.

What do you believe is why KTH ended up in this difficult economic situation?

— KTH has relatively expensive premises compared to others because we are located in Stockholm. The University board had previously wished that the share in relation to our overall costs should decrease. If we had progressed even further in that work, the effect of the increased inflation might have been less severe.

KTH has high premises costs compared to other universities in Sweden. According to KTH's annual report, 18.2% of its expenses were related to the premises in 2022, while the average among all universities in the country was, according to the Swedish Higher Education Authority (UKÄ), 12.2%. Worth mentioning is that some of the premises are sublet. Those costs are included in KTH's economy, making the costs appear larger than other universities. However, Susanne states that KTH still has relatively high costs. KTH's premises rents are automatically increased with inflation, and at this point, no one has missed that inflation has increased sharply in recent years.

KTH forecasts in the materials provided ahead of the national budget by the University board that in 2023, premises costs will increase to 19.8% of KTH's total expenses, an increase of 141 million kr over just one year. Thanks to lower-than-expected energy costs, however, costs are expected to be lower than budgeted. The University board's goal is to reduce total premises costs by 150 million kr annually.

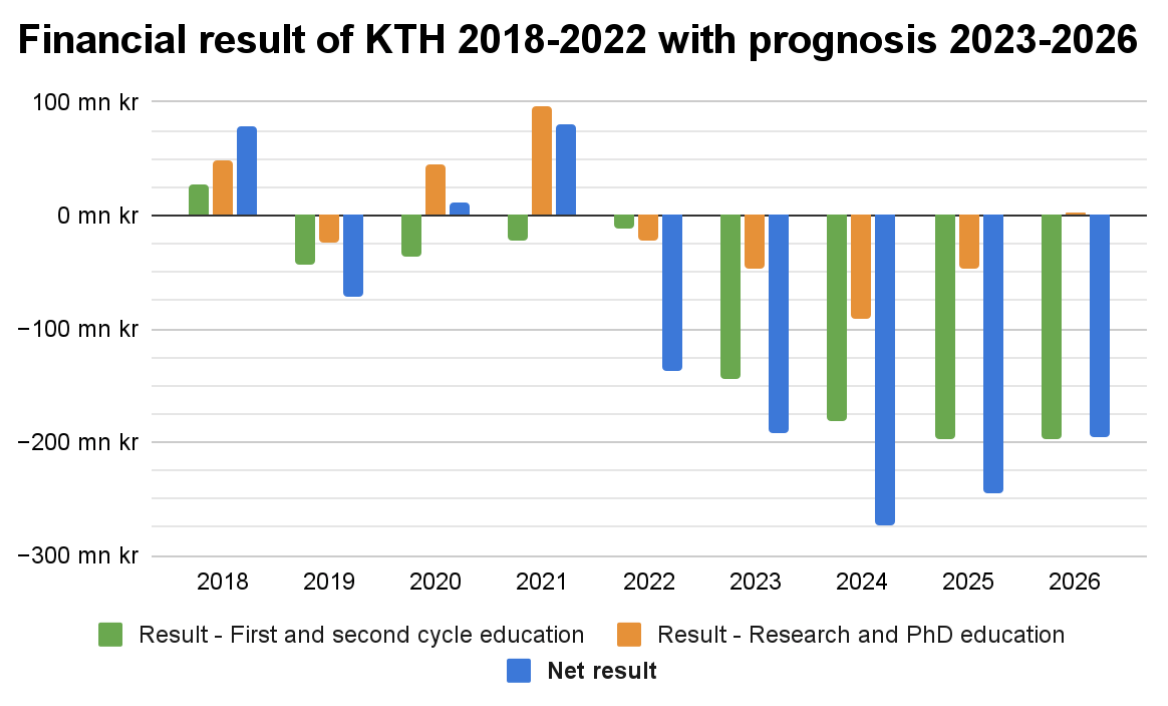

But is it true that inflation is the only cause of the economic issues at KTH? KTH had a negative financial result 2019 for the education area, which has grown over time, from –43 million kr in 2019 to –114 million kr in 2022. According to KTH's prognosis for 2023, the economic result for the education area will be –144 million kr, and if no action is taken, the result will be as low as –198 million kr in 2025 (according to KTH's budget materials 2024–2026). This shows that the economic issues on the education side started before the current inflation crisis.

Until now, we have discussed KTH's result balance, that is, the flow of funds in and out of KTH. But to understand where the concern about bankruptcy in 2026 comes from, we have to look at KTH's saved funds, the so-called agency capital. Currently, KTH has a negative authority capital on the education side, and with the growing negative result, the situation is expected to worsen. At the same time, there is a large, uneven distribution of this capital between the schools and KTH Central.

There is a large, uneven distribution of the agency capital between KTH Central and the schools. Why is that so?

— The agency capital available at KTH is unspent appropriations. So first, we have a big imbalance between research and education. We have a large surplus in research and a deficit in education. Then, there is an imbalance between the schools and KTH Central. There are both pluses and minuses at the schools and a large accumulated negative result centrally. […]

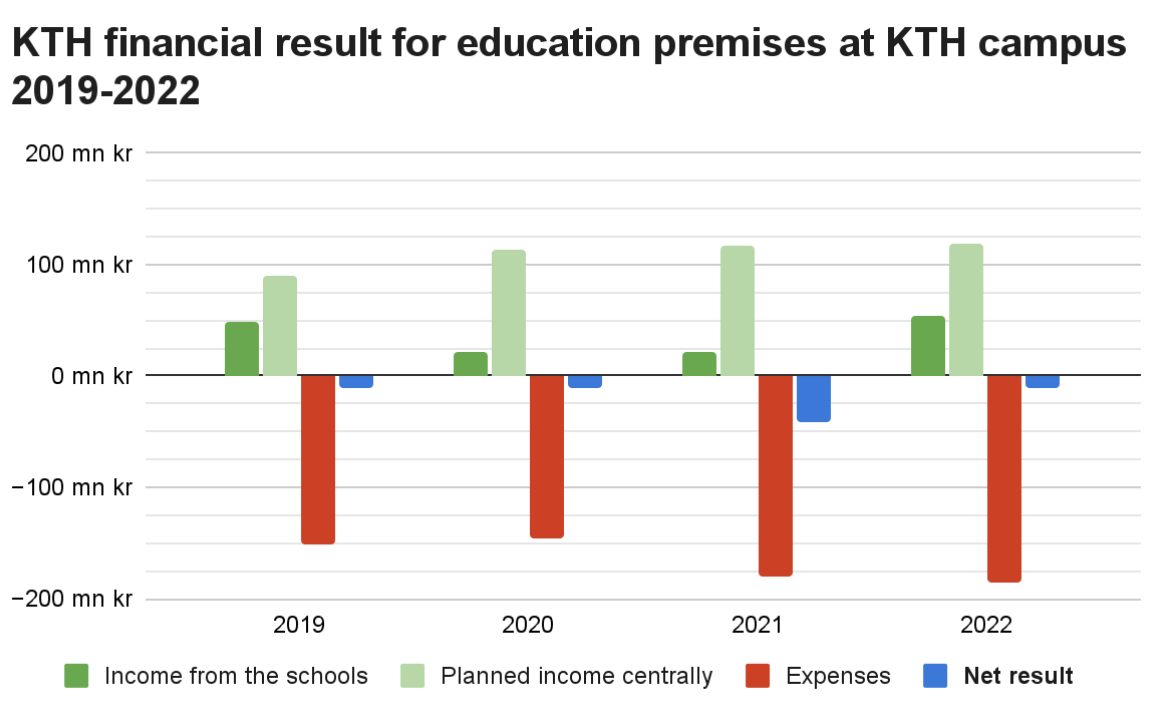

— Part of the GRU funds a school receives should be used for KTH joint learning environments. During the pandemic, when we switched to digital teaching, the schools did not book as many premises as usual, but they still received funds as if they needed to book the premises. Since there were not as many bookings, there was a central deficit.

During the pandemic, KTH switched to distance education, which significantly reduced the booking of teaching premises. The schools pay for those premises based on how much the school has booked, but during the pandemic, the income that otherwise functions as a return mechanism from KTH's schools to KTH central was not available. That is to say, after KTH distributes the education funds, the schools pay back some money, which, among other things, is for using the premises. This has affected the agency capital within KTH.

How did the reasoning go during the pandemic when it became clear that the schools would not book as many premises as they did in previous years? Was there talk that there would be a redistribution in another way?

— The issue was raised, but no one took it further for two reasons. One was that so many other things needed to be done at that moment. The other was that the schools highlighted that, "we may not book KTH joint learning environments to the same extent as we did before, but we get a lot of additional costs because we need to adapt our education [ …]”. It was a pragmatic decision.

Osqledaren got access to the financial results for the educational facilities on the KTH campus, and you can see how the school income decreased significantly in 2020 and 2021 compared to the previous and subsequent years. At the same time, costs for the premises increased.

The education premises are also partially funded centrally. Before the schools even receive money to conduct education, KTH takes a central part to finance central functions, including premises. In 2019, KTH centrally spent 90 million kr on costs for teaching premises and the schools, a total of 49 million kr. The idea is that these two streams should cover the costs, but the income statement shows it is insufficient. Every year between 2019 and 2022 has a negative financial result, further burdening KTH centrally.

So why is the year 2026 on everyone's lips? That is when KTH will run out of total agency capital if the negative financial results continue.

What would the consequences be if KTH ran out of agency capital? Osqledaren asked Susanne.

What would happen concretely if KTH runs out of agency capital and simultaneously has a negative result?

— If we go back to the rumors about KTH running out of agency capital, that is if we do nothing. And we do many different things so we don't end up there. KTH as a university depends on our long-term good and stable financial conditions. The authority's capital gives us the ability to develop, so if the authority's capital were to decrease drastically, it is perhaps in the first stage that we lose the ability to develop. That is serious in itself.

We also asked what would happen if KTH had no more options. In a follow-up email, Susanne replied:

"It is impossible to answer what would happen if KTH exhausted all options. It is so hypothetical that an attempt to answer it becomes pure speculation. When authorities find themselves in very difficult crises, there is usually a close dialogue between the authority and the government/government office, which can result in various measures."

Even if the average student has no reason to worry about bankruptcy, this does not mean that KTH's financial situation does not risk negatively affecting the education and the students. To gain an understanding of how the reasoning goes at KTH, Osqledaren contacted Anna Jerbrant, Head of first and second-cycle education (GA) at the ITM school, for an email interview:

The interview is shortened, edited and translated from Swedish.

Briefly describe your perception of KTH's economic situation at the moment.

— From the information I received via various GA meetings, I have understood that it is problematic and that we all, therefore, have to make an effort to increase our income and, simultaneously, reduce our costs.

Konkret innebär ökade intäkter att KTH det senaste året kraftigt ökat utbildningsvolymen inför hösten 2023. I ett rektorsbeslut som Osqledaren tagit del av framgår det att varje skola fick uppdraget att bygga ut sin utbildning inför hösten 2023. Detta har fyllts både genom ökat antal antagna studenter på programmen men också genom fler fristående kurser. Om du har märkt fler nØllan på campus under mottagningen eller att KTH ger fler fristående kurser i höst än vanligt så är det därför.

In practice, increased income means that KTH has greatly increased education volume for the fall of 2023. In a KTH president decision that Osqledaren has read, it was decided that each school was given a directive to expand education volumes for the fall of 2023. This has been fulfilled through more accepted students in the programs and more independent courses. If you have noticed more new students than usual during the reception or that KTH is offering more independent courses this fall than usual, this is why.

A concept that may be useful to know is the "funding cap". The state sets a maximum grant that the universities can receive to conduct education. For KTH, this is 1.33 billion SEK in 2023. Currently, KTH does not reach its ceiling amount, so there is room for greater income. In 2022, KTH received almost 1.25 billion SEK in education grants from the state.

In the spring of 2023, the schools were directed to increase the education volumes to earn the ceiling "without extra costs". How did you go about increasing the educational volumes?

— We asked all program directors if they saw a possibility of increasing the number of new students without negatively affecting the quality of teaching. Then, all the prefects asked the same thing, and based on that, ITM's head of school (together with the management team) had to formulate a proposal for increased admission numbers for the fall semester of 23.

The other way that KTH is trying to solve its negative financial result is to reduce premises costs. Last spring, the ITM and EECS schools (responsible for campus Södertälje and Kista, respectively) were directed to investigate the pros and cons of moving the activities from those campuses to Valhallavägen and Flemingsberg.

When Osqledaren asked Anna what the consequences of a campus move would be, she referred us to the ITM school's report that they have produced. If you are curious, the ITM and EECS schools' reports are available on KTH's public staff website.

Many students are concerned that there is already a shortage of study places on the Valhallavägen campus and that a campus move would exacerbate that problem. Both the ITM and EECS schools' reports confirm that concern. From the ITM school's report: "With a simplified model of reality where a student uses a study place for a little over 4 hours a day [...] we believe that an additional 200 study places will be required on the KTH Campus." (page 13). The EECS school's report is even more gloomy: "About 570 places for self-study [at Campus Kista] will be lost in a move to the KTH Campus." (page 4).

The reports also highlight positive aspects of a possible move, and there is a hope that this could be a chance to develop the education at KTH. The question is whether it outweighs the negative aspects.

An ongoing project at KTH is Framtidens utbildning, a major investment in developing the education at KTH.

Do you believe that KTH's financial challenges will affect the project?

— I hope that the hard work we all have to do to bring KTH's finances into balance does not mean that KTH's management and employees do not have the opportunity to prioritize the work needed for Framtidens utbildning as well. Right now, however, there are no indications that KTH's financial challenges will affect the Framtidens utbildning program in a negative way.

The future of Campus Kista and Södertälje will be decided at the university board's meeting on November 22. Only then can we know the consequences of KTH's financial problems for the students on those campuses. Of course, Osqledaren will be there and report as soon as we know more.

But regardless of how it turns out, the education and the students will be affected, in both small and large ways. No one wants to be in this kind of situation, but in this situation, it's probably best to just tough it out. What we, as students, can do is demand from KTH that this does not happen again.

Publicerad: 2023-11-07