The nuclear reactor that turned into an opera stage

Alexandra Andersson - Authoralexandra.andersson@osqledaren.se

Tingyu Su - Illustratortingyu.su@osqledaren.se

Martin Hellström - Photographerpress@kth.se

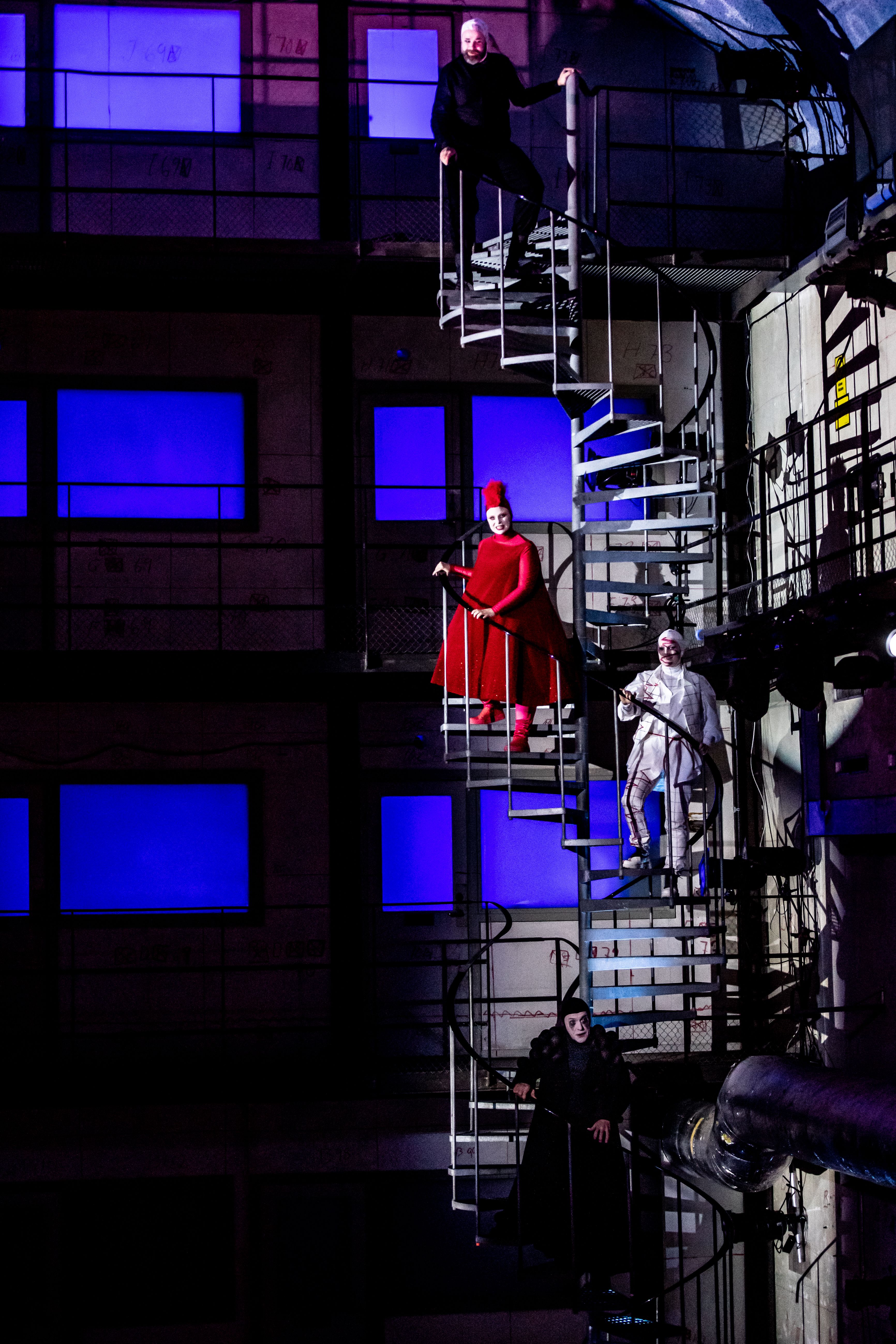

In December, Sweden’s first nuclear reactor 25 meters below KTH transformed into the stage of the opera “The Tale of the Great Computing Machine”. Osqledaren was there to learn more about the work behind the opera and to experience a show combining the classical opera art with new technology in a truly unique place.

It has been one year since I was in KTH R1. Back then it was quiet and dark, but when I take the elevator 25 meters down in the reactor hall this time, it is buzzing with life and movement. In the provisional dressing rooms the makeup is touched up, in one room the singers are heard practicing and me and the producer Terese Lindström from Vadstena-Akademin are almost overturned by Åsa & Carl Unander-Scharin who make some last reconciliations. They have written the libretto together with Nils Spangenberg, composed the music, made the choreographies and directed the opera “The Tale of the Great Computing Machine”. Tonight is the dress rehearsal.

The libretto is based on Hannes Alfvén’s fictional bok “Sagan om den stora datamaskinen” (Eng: “The Tale of the Great Computing Machine”), which was published first in 1966. Everything started when the anniversary for Hannes Alfvén’s Nobel Prize was approaching:

– In spring 2019 a discussion had begun on KTH about that in 2020 it was 50 years since Hannes Alfvén received the Nobel Prize, says Leif Handberg. He is the superintendent of KTH R1 and the initiator of the opera. It was when the anniversary was approaching he heard about the unfinished opera. In the afterword of the new edition of “Sagan om den stora datamaskinen”, Alfvén wrote about how his book was planned to become an opera already in 1968.

– Karl-Birger Blomdahl wanted to make an opera of it, so he started to write a libretto. But in the middle of the process he got a myocardial infarction that he did not survive. So there was no opera.

Photo: Martin Hellström

But 54 years later the opera finally becomes reality, and despite Alfvén’s book being old, the timing is perfect. “Sagan om den stora datamaskinen” is about how the computer takes over and outruns the human:

– He is pretty spot on in his predictions regarding what will happen with smartphones and AI, even though he doesn’t use those words. When you read you don’t know if the narrator is a human or – as we would call it today – AI, and that is the only character, says Leif and describes how Carl and Åsa have transformed the special book into an opera:

– We have five singers who portray humanity, so they are named after our atmosphere – Argon, Hydrogenii, Oxygeni and Nitritio – and Carbon, which is important for organic life. And then we have the narrator Computa – the computer system – that is everywhere. Partly inside our organ, and Computa is also portrayed by our dancer and towards the end we have robots that play instruments and they are also this character.

In the opera, in addition to singers and musicians, two robots of the type YuMi that has been borrowed from KTH’s strategic partner ABB are participating:

– One might think that it is a two-armed robot with no head, but it’s actually two one-armed robots that are connected, Leif explains. Either it has two left arms or two right arms, so it’s not symmetric. It’s a collaborative robot, so it can work close to a human.

– But with two left- or right arms you must design the pattern of movement in a certain way. A computer science student – Elsa Benzinger – has programmed it based on Åsa’s instructions, Leif explains and gestures with his arms to illustrate the differences between a regular industrial robot and a choreographed opera robot.

– The robots are really good because once they’ve “learned” they do exactly the same all the time. Towards the end they play the instruments that the humans play at the beginning of the opera.

Leif, Terese and I are sitting up in their office while there is a music rehearsal down in the reactor hall. When Leif got to hear about the unfinished opera he directly contacted Carl and Åsa, and they suggested they should ask if Vadstena-Akademien wanted to participate, and then it all began. In total there are about 35 persons working with the opera.

– One of our purposes is to make a lot of newly written music to develop the opera art, and then this was a good fit, Therese says. This is both newly written and new technology and a completely different place than we are used to. It’s both development and skill enhancement for us.

Photo: Martin Hellström

And it is indeed something special about the place.

– The hall down there is like a church hall with its acoustics, Therese describes.

– That it is on KTH, in the world’s coolest reactor hall to which you must go down many meters under the ground, makes this cool in another way, exclaims Nora who has just taken a seat at the table where we are sitting. She is a musician and plays the string instrument lirone in the opera.

– There is something thrilling with the history; that Sweden did research here, which lead into the atomic age in the 50-60s, Leif says. But it’s also a weird, large place 25 meters down in a mountain and that alone makes it raise questions. When the opera art was born in the 17th century opera was in the forefront of artistic development, but then I would say that we got stuck in the big classics. But this is a way of bringing back the exploring part, now that we’re bringing in so much technology.

The idea that opera would be harder to appreciate than other forms of culture is not supported by neither Terese, Nora or John Erik Eleby, who also has joined us around the table. He is one of the singers and plays the role of Carbon in the opera.

– It’s a prejudice that it’s hard, he thinks. It’s just to go there and absorb what you get and then you maybe don’t like it, but that’s how it is with everything.

– I think many people who go to an opera have already decided that this is something special that you don’t understand, and then you think too much instead of just feeling, says Terese.

– If you watch football and don’t know the rules, can you still enjoy it? It’s not harder than that, Nora adds.

When Nora and John Erik were asked to take part in the opera, they did not hesitate to say yes.

– I who work at an opera usually cannot get away from there, but I managed to be free to be able to do this, tells John Erik. At Kungliga Operan (Eng: The Royal Swedish Opera) you work as in an opera factory, delivering operas, always with the same setting. Here everything is created from scratch, the set is new and nothing has been done before.

Nora agrees that this is different compared with what they usually participate in:

– I play an instrument that is for renaissance- and baroque music normally, so it is incredibly unique to be able to speak with the composer at all. They are usually stone-dead.

Everyone agrees that the biggest challenge with the project is all technology:

– There are many components, says Leif. What do we do if something is not working? At what point should we step in and break?

– We are very analogue in Vadstena-Akademien, with operas and instruments that are true to time, Terese explains. Here there are advanced systems, but we have great stage masters, programmers and a whole bunch on the technical side.

It is a few hours before the dress rehearsal and only a few days until the premiere on the first of December.

– Yeah, how did this happen? This year for example the month of October just disappeared, says Leif and Terese agrees. At the end of September we had plenty of time and full control, and then suddenly it was November and no one understood what had happened.

Despite that, the atmosphere in R1 is calm and relaxed.

– It feels great, says John Erik.

– Yes, it will be beautiful, says Nora.

– I can go out if you want to say something else, Leif concludes with a smile.

* * *

A few days later Osqledaren is back in R1, which has been transformed into a perfected opera scene since I last was there. “The Tale of the Great Computing Machine” attracts a broad audience; among the hundreds of people in the audience there is everything from adolescents to families to elderly couples. When the lights go out, all eyes are directed to the scene on the other side of the reactor pit and the dystopian story about the race between the human and the computer begins.

We are immediately reminded of being in a former nuclear reactor when the opera begins dramatically with something being unwind in the reactor pit by a crane. It is the same crane that was used when the reactor was built and dismantled, and to lift the uranium rods out of the reactor during inspections. The rooms where the researchers had their offices has turned into coulisses and from there the singers make their entrance.

Photo: Marc Femenia

The story about Computa and the humans is told through the song, dance and music. The doomsday feeling is close, but on a few occasions, unexpected lines make the audience laugh. Something is happening all the time; projections on the walls and floor make the eyes of the people in the crowd wander all around the room, the lighting is effective and the self-playing Skandiaorgeln (Eng: The Skandia Organ) contributes with many surprises. At the same time, the wingbeats of history echo in the hall, in powerful contrast to the modern opera that labors with the integration of technology in art. Everything ends with the dancing robots – a unique element that captures the very essence of the first ever opera in Sweden's first nuclear reactor.

– We do have a 200th anniversary for KTH that is fast approaching. It’s only five years away so the planning has to start now, said Leif when I a few days earlier asked him if we can expect similar events here in the future. After this opera I look forward to see what further potential is hidden 25 meters below the ground at The Royal Institute of Technology.

Publicerad: 2023-02-21